Turning Geographic References into Maps with Recogito: Part 1(of 2)

By Caroline Diemer

Note: This is the sixth in a series devoted to the project “Narrative and Geography in the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor”.

First post (“place” in history) here; second (“place” in narrative) here; third (how we divided our text) here; fourth (how we coded “geography” in our text) here; fifth (how we organized those codes) here.

This blog post will follow very closely the “geographic references” that we have implemented in MaxQDA (as discussed in the previous blog post).

With the easily accessible, incredibly detailed and accurate maps constantly available to us in our daily lives, we must always keep in mind that we do not have the same mental visualizations of the physical world as would those we study in the past (for this project specifically, ninth-century Byzantines).

When reading such geographic reference-rich texts as the Chronographia, it is hard to understand the world that is being constructed for the contemporary (ninth-century) reader. This is due in part to the disjunct created by our own reliance on visualizing the world as maps, but also to our unfamiliarity with the names and connotations specific places would have had for a ninth-century Constantinopolitan.

Our tool of choice: Recogito

To understand the geography of the Chronographia, we are using Recogito, a program which visualizes, or actualizes, written geographies that can cause the modern reader confusion. Why was Recogito the right source for our purposes?

Recogito is an initiative of the Pelagios commons, a text annotation tool for creating maps by turning “tags” of geographic references in a text into either points or polygons (the program’s way of representing a region) on a geographic projection.

The placement of the points, as well as the shape of the polygons, come from Pelagios Map Tiles. Recogito collects its place data from the community-built and rigorously edited online gazetteer Pleiades, as well as the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire (DARE). As such it not only has the virtues of being online and open access, but is also backed up by the most up-to-date and rigorous geography of the ancient and late antique world available.

Recogito works to put texts in direct conversation with all of this geographic data.

For instance, Recogito has a function for tagging/annotating all references in a text. For example, when I tag Constantinople, I am given the opportunity to tag all the mentions of Constantinople in the text I am working with.

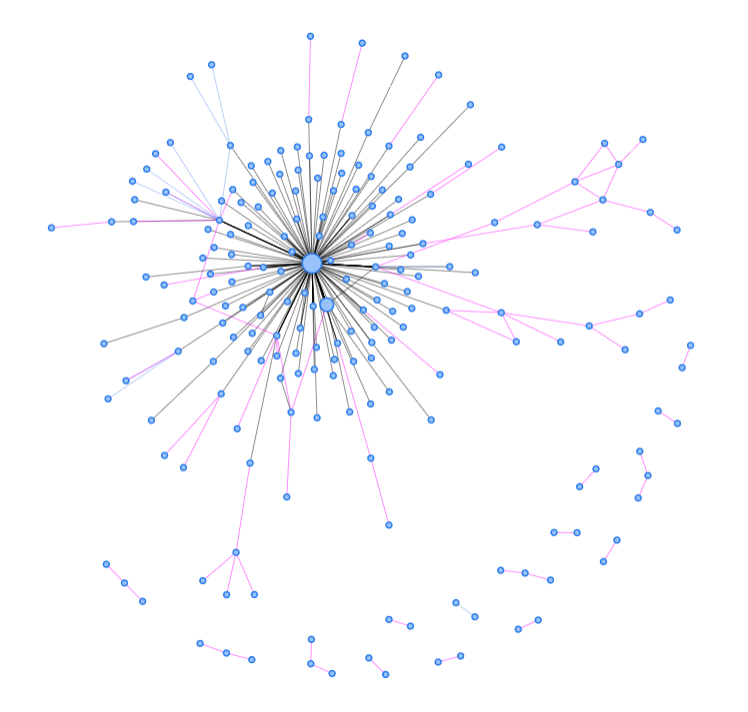

After I have finished my tagging, Recogito will generate a map that represents points as circles. A point with many tags will be larger than a point with very few (though there is a small standard size, so depending on the range of the distribution of points, points with a few tags may be the same size as one with only 1 tag).

When you click on one of these circles (or “points”) Recogito shows you all the different terms from the text that we have located at that geographic point. This is especially important for our project as this feature allows us to see who is mentioned in association with a specific place. That is, many of our geographic tags are what we have called “implicit geography” – such as bishops who are tagged with the city of their see.

Clicking on a point also displays a portion of the specific passage that point comes from (and if multiple passages, how many), as well as the number of tags for a place.

Both of these features help to show what has determined the nature of the site’s role for this section of the text. Such as: Is Alexandria, as a city, mentioned a lot or are there a lot of people from Alexandria doing things?

Both of these features help to show what has determined the nature of the site’s role for this section of the text. Such as: Is Alexandria, as a city, mentioned a lot or are there a lot of people from Alexandria doing things?

The Process

- Splitting up the Chronographia into the different emperors

We split up the Chronographia into individual text documents for the reigns of each emperor. We did this first because it is an extremely long document.

But second (and most important for our analytical questions), dividing by emperor allows us to compare the differences between emperors. We are interested in seeing what types of geographies appeared with each emperor. Where are the geographies of concern? Is there one place mentioned more than the others? Is each particular reign more region-based or city-based (as we found when comparing Diocletian to Constantine)? What people groups or regions did the Chronographia consider to be of greatest concern under each emperor?

- Uploading the Documents, and Recogito’s self tagging

Recogito has a feature whereby, when you upload a document to the program you can allow it to automatically tag any place it can recognize. In theory this would be an incredibly helpful feature, considering about 25% of the things I tag in Recogito are well-known places. As already stated, Recogito draws place-names from several platforms, not just from Pelagios map tiles, but DARE (Digital Atlas of the Roman empire) and Modern Geonames. It seems that with the automatic tagging feature, however, Recogito currently does not use Pelagios and DARE but only Geonames, or at least prioritizes this database. This is a problem because there are many places around the world which share names. One example of this is Antioch. Syrian Antioch is an often mentioned city in Recogito because it is one of the bishops that is included in the rubrics. But instead of tagging ancient Antioch, Recogito automatically tags the Antioch in southern California, half a world away from where we needed it.

This is what happens when Recogito autotags all of the Chronographia

This is what happens when Recogito autotags all of the Chronographia

This problem arose with the majority of the  automatic tags. Because Recogito does not have any way to mass edit tags, I would have to go through and fix each tag individually. So instead of letting Recogito try to automatically tag places for us, we had to start with a clean slate. This required us to unclick the automatic annotation button during the uploading process.

automatic tags. Because Recogito does not have any way to mass edit tags, I would have to go through and fix each tag individually. So instead of letting Recogito try to automatically tag places for us, we had to start with a clean slate. This required us to unclick the automatic annotation button during the uploading process.

- With and Without Rubrics comparison

Besides comparing the narratives of different emperors’ reigns to each other within the Chronographia, we are also ultimately interested in comparing two versions of the Chronographia. The main difference between the “geography” of the two versions of the text is quite significant, more so than one would guess as the bulk of the text of the Chronographia is exactly the same in both.

The one version – that which is familiar to historians of Byzantium as the version in all the critical editions and translations – has what we call “dating rubrics,” which are not red-lettered headings, but a list at the beginning of each new entry with the current emperor, the emperor of Persia, and the bishops of Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and then Antioch.

The other version of the Chronographia (preserved in the ninth-century manuscript Paris BnF Grec 1731) lacks this rubricated system of dividing up each entry.

Since our interest is in studying geographical mentions or references in the Chronography, the difference between these two is significant as the one version initiates each entry with this “dating rubric” rote-mentioning seven places, whereas the other version has none of these.

Thus far, all of the Chronographia with rubrics has been mapped in Recogito. A selected number without rubrics has also been mapped. At this mid-way stage of our project, comparing the two versions allows us to already see exactly what a difference these references make in the geographic “pictures” created in the two versions of the text. The difference is immediately apparent, and quite visually striking:

The Geography of the Reign of Constantine I according to the Chronographia (305-335):

The Geography of the Reign of Constantine I according to the Chronographia (305-335):

(left) with dating rubrics, (right) without dating rubrics

This is, however, preliminary and is merely a preview of some of the analyses we will use Recogito to perform on the narrative of the Chronographia.

In our second post on Recogito, we will describe some of the procedures and problem solving techniques we have developed in order to use this tool to map our text in a manner aligned with our research questions and agendas.