By: Diana Tran

Fall 2024

Methodology:

Event Types Categorization

Tagging the chronicle entry involves splitting it into different events. Events are specific instances within the text that have a clear start and end. X happened. Then Y happened, and so on. The methodology of tagging events was created by Daniel Feldman and Arla Hoxha. To reiterate, an event is a specific moment within a chronicle entry based on the text. To organize events and transform these events from qualitative data to quantitative data, the sub-object ‘event type’ was created.

An event is suggested to only have one event type labeled per event. The event types created by Daniel Feldman were:

- Astronomical phenomenon

- Natural Disaster

- Death of aristocracy

- Death of religious leader

- General Assembly

- Religious

- Political event

- Military Campaign

A discussion of the event types revealed problems with the methodology of the labeling. For example, religious leaders were oftentimes aristocracy, thus labeling for death of religious leader came with the implicit labeling of death of aristocracy – a double labeling that is unnecessary and added fluff to the data once mapped out. A general assembly would be considered as a specific political event, yet it was labeled separately. The largest issue came to be the political / religious event types that implied an event may only be religious or political. The separation of state and church is a modern concept that, when applied to medieval times, applies a modern bias to the data. The issue of the split of religious and political event mimics the issue that comes with labeling the death of aristocracy and death of religious leader – one follows the other, making the manufactured split superficial and inaccurate.

A proposed change in the methodology to address these concerns would be to scrap the labels political event, religious, and general assembly. It would also combine death of aristocracy and death of religious leader into a general label of death. The labels of astrological phenomenon and natural disaster would also be combined into the new label phenomenon which would encapsulate both.The new labels, in accordance with the parameters of only one word describing each event type, are tentatively named:

- Mission (External)

- Petition (Internal)

- Campaign

- Phenomenon

- Birth/Death

- Office (previously titled Succession)

- Dispute

- Celebration

- Commentary

- Construction

Mission is a replacement for ‘political’ which specifically is for interactions that occur between two emissaries of sovereign nations, i.e. legates of the Church or ambassadors of Emperor Basil being received by Louis the German. A way to distinguish between Mission and Petition is to ask if the two or more emissaries interacting are from the same nation or different nations? If the answer is of different nations, then the label Mission should be applied. The concept of foreign diplomacy is another way to explain the parameters of this label. ‘General assembly’ is a keyword typically indicating that the meeting is one that deals with foreign embassies as well as domestic ones.

Petition is the other replacement for ‘political’ which should be applied to interactions that occur between individuals of the same nation, i.e. Bulgars going to Michael (Boris I), their old king or ‘King X held meeting’. The concept of domestic diplomacy is a way to explain the parameters of this label. An assembly or a meeting without the adjective of ‘general’ is typically a sign that the interaction between two individuals are domestic rather than foreign.

Campaign is the replacement for Military Campaign. Campaign is meant to label events that involve battles and wars between two established states. These two states should not be connected to each other via vassalage at the start of the battle – those should be labeled ‘Dispute.’ A question to ask when conceptualizing events that should be labeled ‘Campaign’ is whether the fighting involved is foreign or domestic. If it is foreign, then ‘campaign’ should be the event type label used. Though it may not be clear without background information, a quick Google search to assess the relationship between two peoples or states during a specific time could be useful in discerning the difference if needed.

Dispute should be used to label domestic conflicts within empires or between a sovereign state and its vassals. Conflicts with the church should be labeled as ‘dispute’ as the church is an international entity rather than a people or state concentrated within one area. Dispute can additionally be used to label events that deal with disputes that do not have a battle component to them. The verb ‘rebel’ is a typical indicator of when this label should be used, as well as nouns like ‘insolence’. Of course, the surrounding context is also important.

Phenomenon is a combination of the previous labels of natural disasters and astronomical phenomenon. Discussion was held to determine that separating the two seemed redundant especially as the labeling method would be similar – rather than the subject – verb order, it would instead be the verbal noun or noun of what is happening. Instead of ‘floods began’ with the emphasis of the verb being ‘began’, it would be ‘flooding’. Another example would be with the phrase: ‘there were earthquakes.’ Instead of ‘Earth quaked’, the labeling would be ‘earthquake.’ Rather than ‘sun eclipsed’, the labeling would be ‘sun/solar eclipse.’ However, if there is a verb that goes well with the phenomenon occurring, exceptions can be made, such as with ‘comet appeared.’ It is based on the surrounding contexts.

Birth/Death is rather self-explanatory – this label should be used in the case of a birth or death, It applies to all – the identity of the one who has died or been born– whether they are aristocracy or an individual who held religious office or a commoner – does not affect whether an event receives this label or not.

Office/Succession is a label that should be used in the case of a change in office whether death related or not. Office/Succession does not need to only be for kingship, but also ascending from kingship to emperorship or bishop to archbishop [for example]. The label should only be used when the change of office is the focus of the event, however. If a person is mentioned to be the heir or successor of X position, that event should not get the label unless the emphasis is on the change of office. As an example:

Despite this event mentioning the concept of succession, the focus of this event is in actually the rebellion of the Sorbs and Siusli – thus, this event should be labeled as ‘Dispute’ for its event type.

Celebration is a label that should be applied to any holiday, religious [Lent, Christmas] or not, that occurs as well as any feasting due to a successful campaign. It can be considered the new ‘religious’, like how Diplomacy could be considered the replacement for ‘political event’ due to how many holidays are religious in nature. Many events that will have the label of ‘celebration’ will likely be due to holidays, however, this should not dissuade the tagger from not tagging festivities that are not religious or specific to holidays. ‘Celebrate’ is a common verb used within events that should be tagged as Celebration.

Commentary is a label that should be applied to when the writing of the text changes to refer to the reader or author themself. A fuller name for this label would be commentary by author, which is also self-explanatory. Keywords that indicate where this label should be used are “I” and “we.” Another indication that this tag should be used is when the author reflects on an individual’s (within the text) actions and expresses their opinion.

Construction is a label that refers to the construction, reconstruction, or destruction of a building, wall, or anything that can be built (such as a castle). It should especially be used in cases of places that are named, however, unnamed places that are built or deconstructed can also have this label applied to it.

With this new methodology in event type labeling, the misrepresentations created by the political event / religious labels are diminished by erasing the modern lens previously placed upon the labeling of event types. The focus is put on what happens within an event rather than how an event is conceptualized to the modern tagger. An emphasis is put instead on the observations of the main verb and surrounding context. Additionally, with the old methodology, the deaths of the common people, which are sometimes mentioned as the focus of an event, did not have an accurate label for event type. The issue of aristocracy/religious death is also avoided by having two categories that encompass death for all as well as the succession of either. The rationale behind combining ‘natural disaster’ and ‘astrological phenomenon’ is that both are natural phenomena, thus separating them serves no purpose. The events labeled ‘natural disaster’ and ‘astrological phenomenon’ are near identical in description and presentation within the chronicle as is:

The issues that come with this new methodology are that when it comes to rebellions that are successful in nature, one has to be cautious with the shift that comes. For example, within 898 AF3, other political entities interfere within – the question asked then if the event in which it is mentioned is still a dispute – a domestic conflict – or if the interference of another political entity turns what was a dispute into a campaign?

There is also trickiness with the ‘Death/Birth’ (which was once only Death) and ‘Office’ labels, as the previous logic behind office was that births are important to succession thus, births should be labeled under Office. However, the discussion revealed a possible modern bias with assuming that every birth leads to or affects succession, thus, birth became attached to ‘Death’. The question then comes to be if deaths and births should be labeled under the same label, or if another label should be created in lieu of combining.

Other labels that may be worth adding are building/construction to represent the construction of buildings or walls, as historically speaking, monuments represent political power and may become significant in the upcoming years, as well as ‘author’s note’ for when the author(s) of Annals of Fulda interject their opinions into the chronicle, such as in 874 AF2, AF3.

This updated methodology aims to address some of the concerns discussed about the previous methodology, though it comes with its own set of problems. It is still in the process of being revised to become more aligned with the goal of Chronicles. Further discussions and research will be conducted over the summer in order to refine these categories with the goal of removing modern bias within these labels while also creating enough labels to encompass the types of events that happen within these chronicles. This is imperative to creating a methodology to quantify qualitative data that is the goal of the Traveller’s Lab.

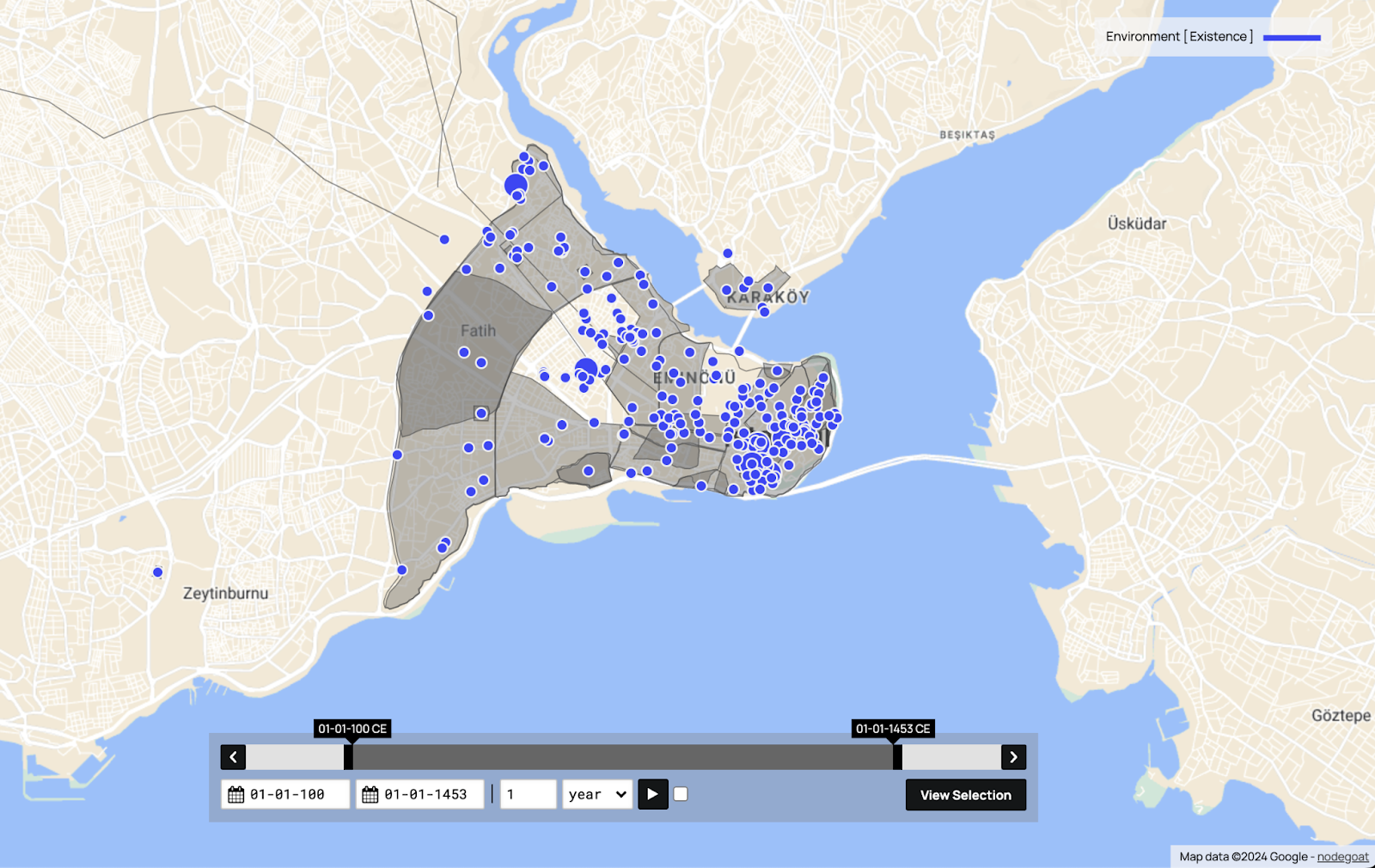

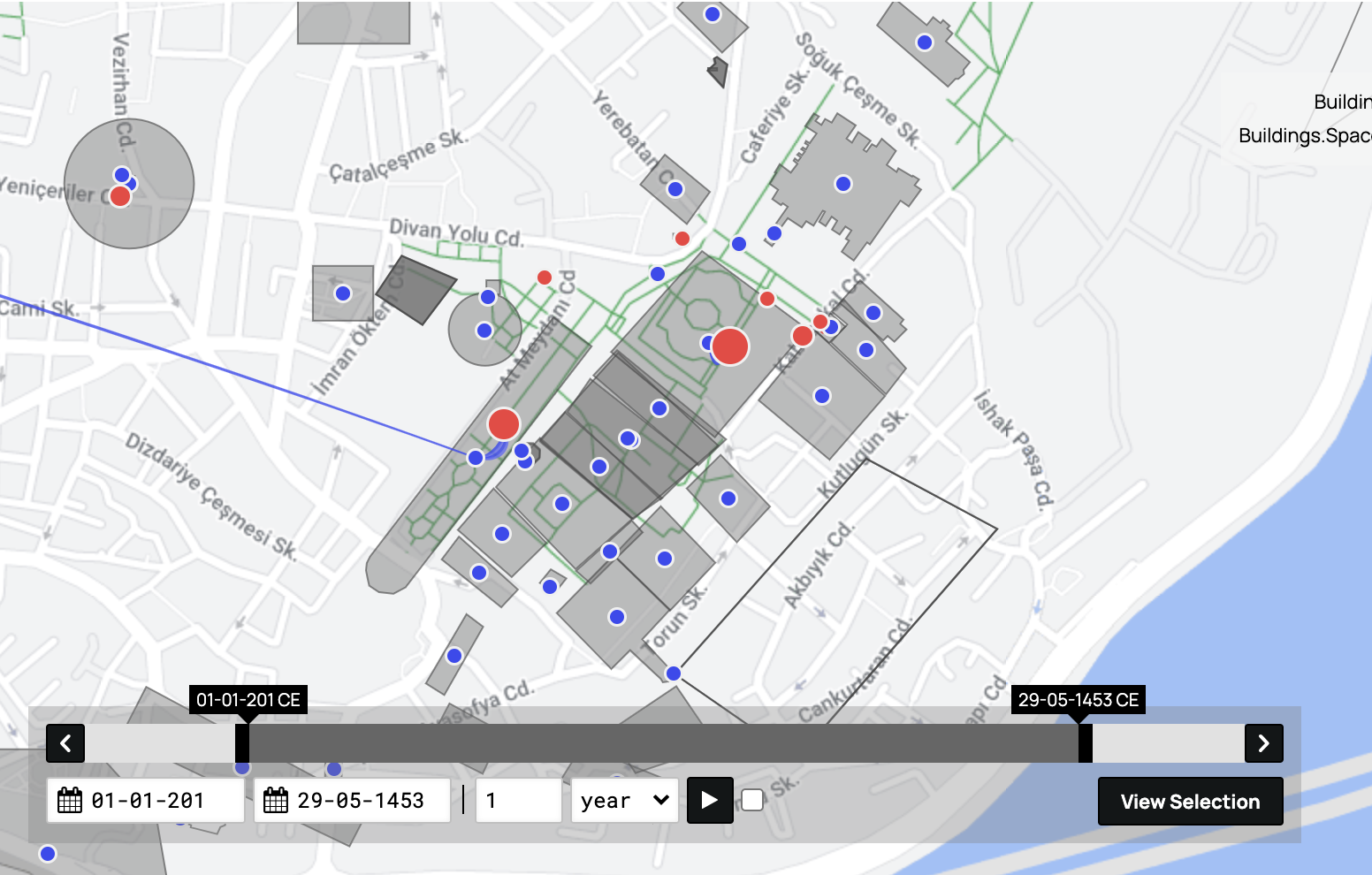

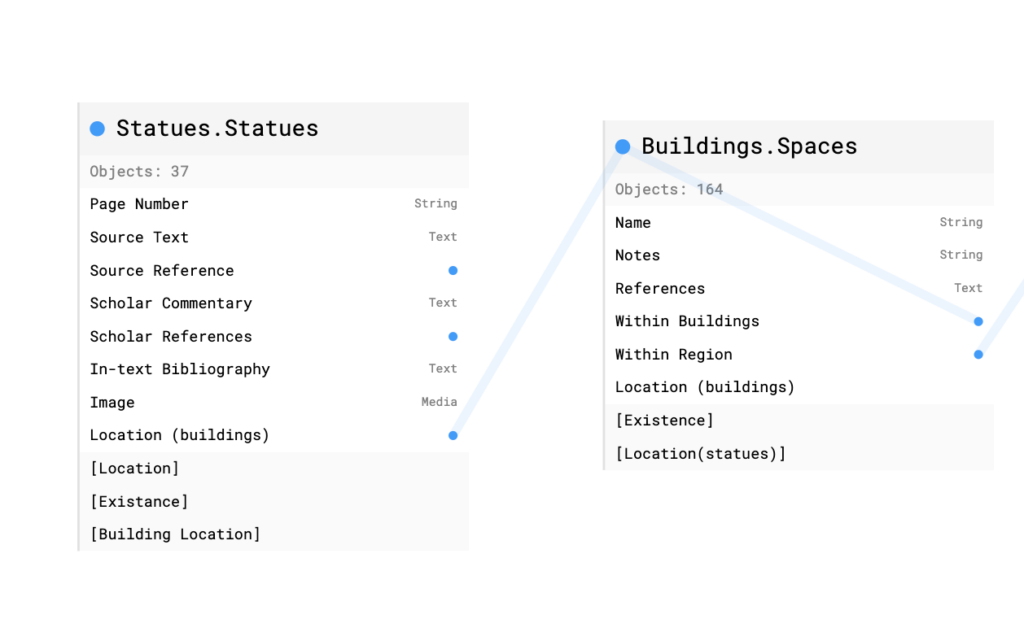

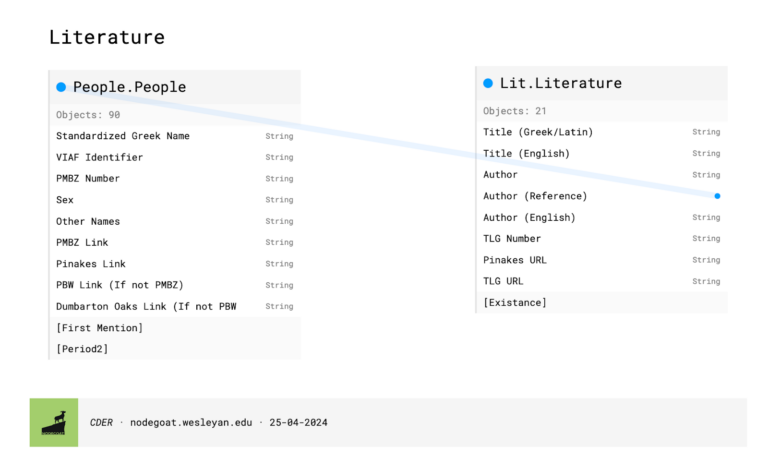

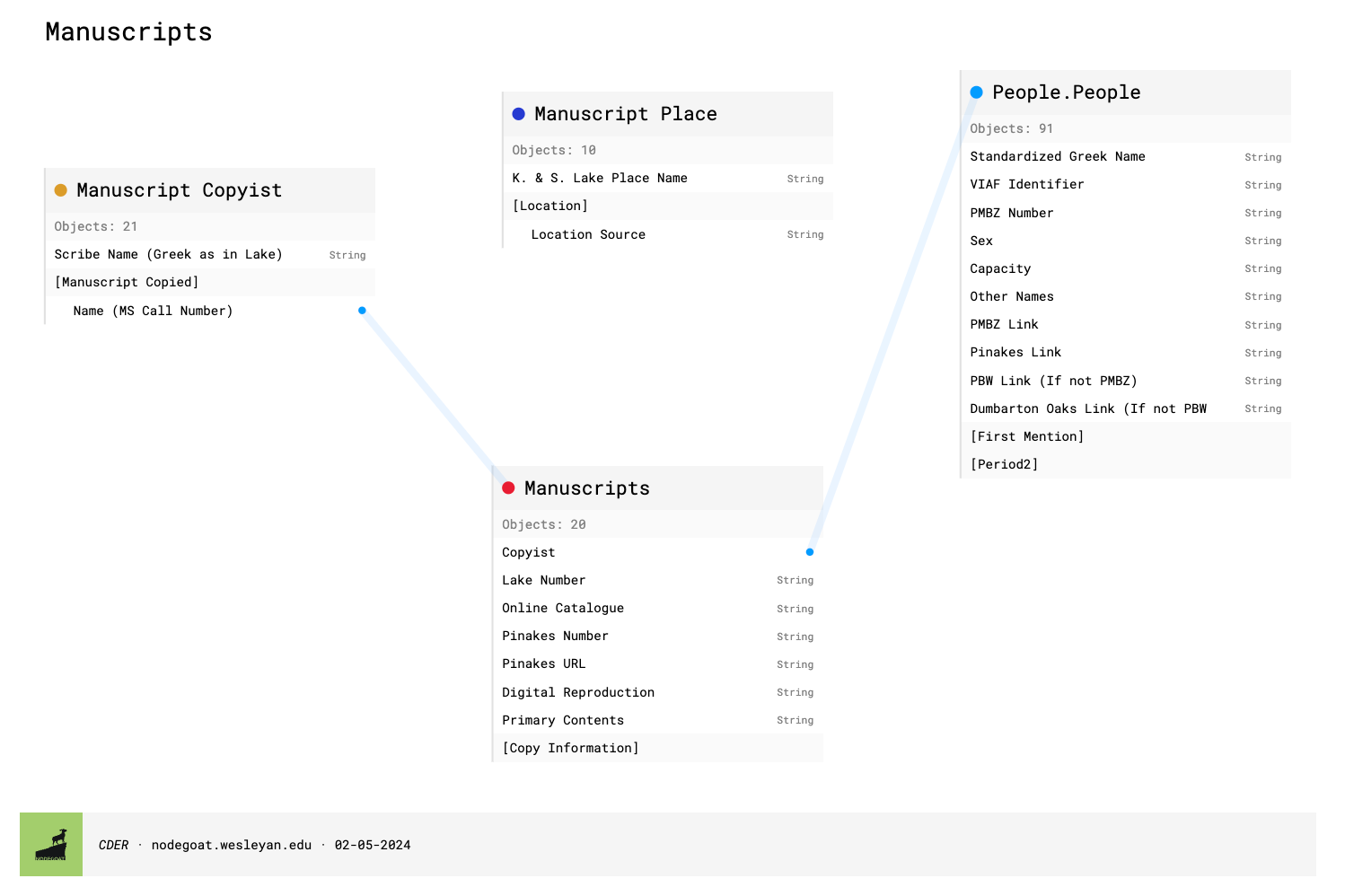

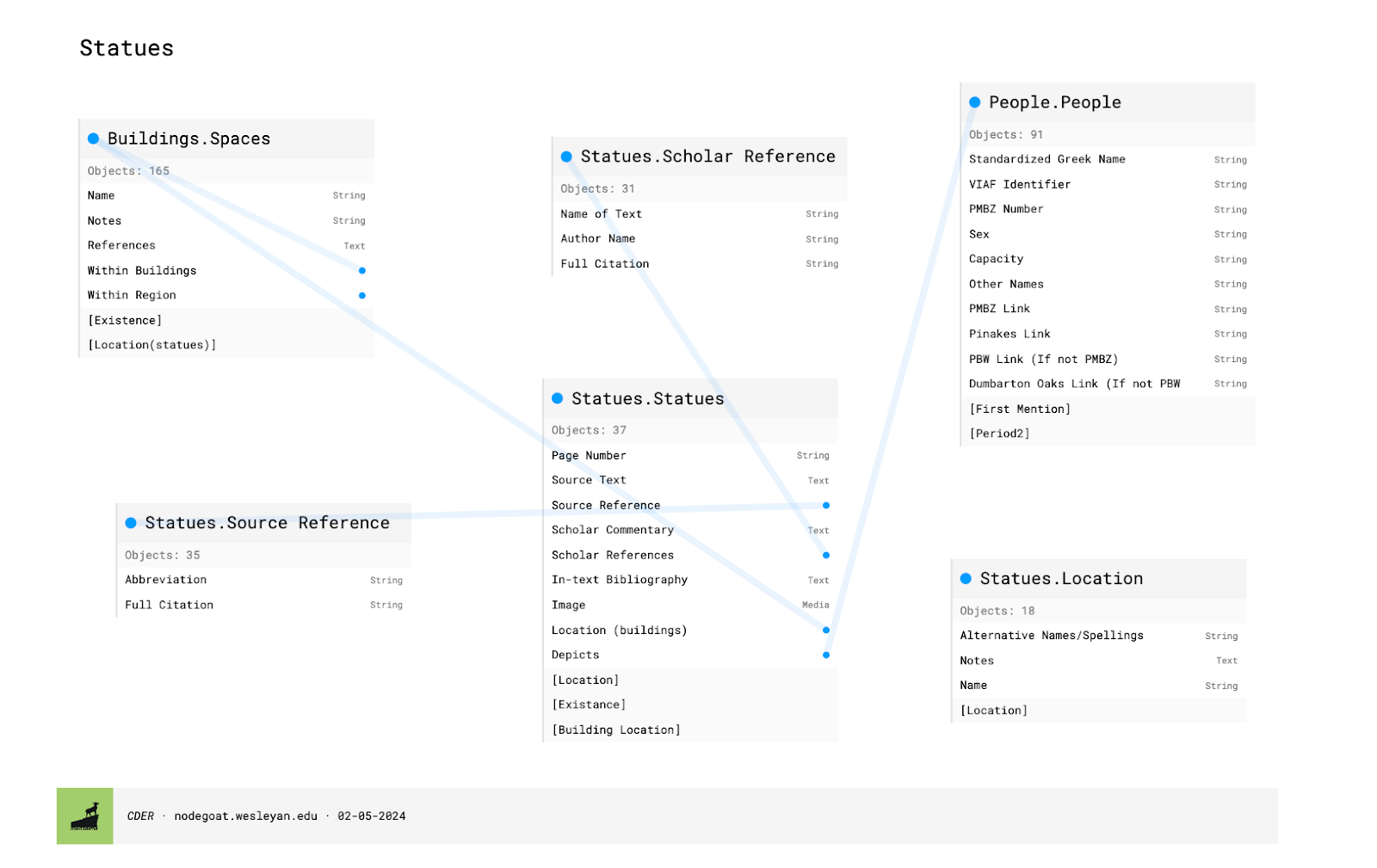

t are researching sources and incorporating them in the platform, and compiling data in the platform, with Professor Torgerson’s guidance.

t are researching sources and incorporating them in the platform, and compiling data in the platform, with Professor Torgerson’s guidance.