By Kathryn L. Jasper

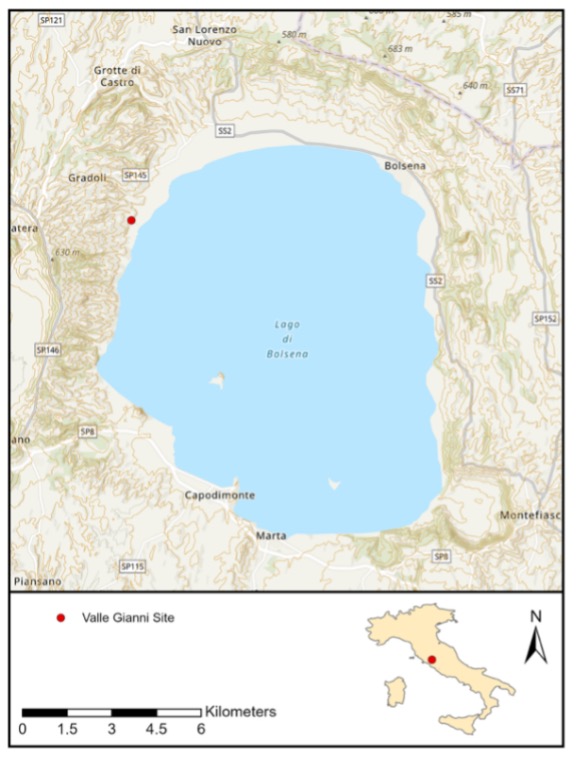

Since its inception the Valle Gianni Field School (or Northwest Bolsena Archaeological Project – NBAP) has found new ways to collaborate with undergraduate students in the archaeological excavation of an imperial Roman villa. In the past three years that collaboration has included Wesleyan students trained in the Travelers’ Lab. The Valle Gianni excavation expands the historical narrative of central Italy during and after the Roman period by focusing on a region that has received little attention from archaeologists and historians. The published report of the initial seasons is available from Fasti Online. The excavation is funded by an ARCS research grant from Illinois State University.

What is the Valle Gianni Excavation?

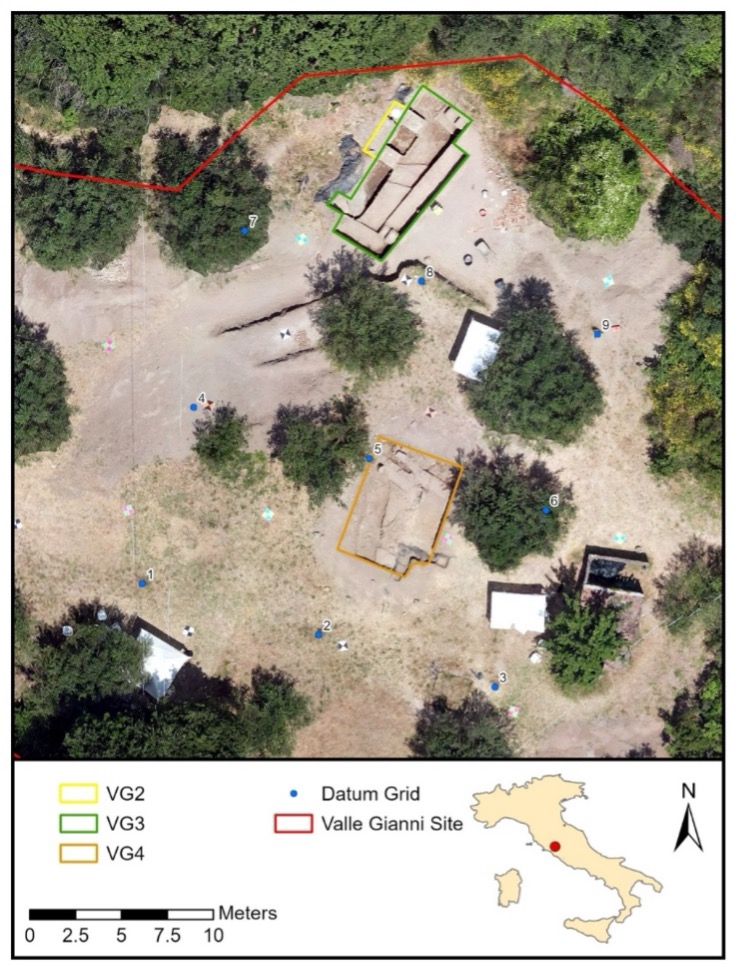

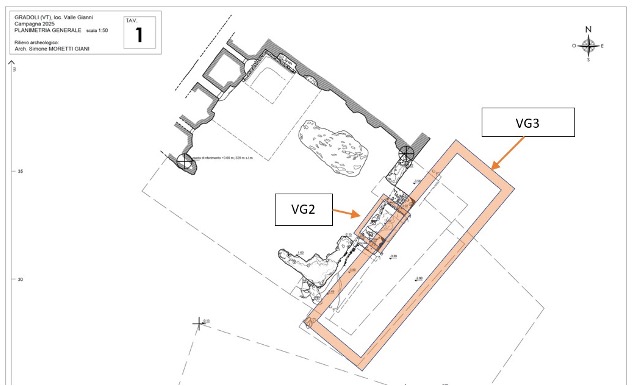

The archaeological site of Valle Gianni is currently defined by two primary features—the partially exposed remains of a monumental fountain from the Roman imperial period, and some recessed vats associated with wine production. When working on site students experience every part of the excavation process (survey, mapping, excavation, ceramic analysis, etc.). Students thereby actively contribute to recovering the now-lost relationship between the landscape of this region and the centuries of human actors who lived, farmed, and built residences there.

Direct Student Involvement

One of the most exciting and innovative aspects of this project is the direct involvement of undergraduate students in not only the excavation work but in data creation and analysis. The interdisciplinary research-teaching model of the Valle Gianni Field School unites humanities and STEM fields by bringing together the diverse expertise of faculty instructors from four different departments. For students this means an opportunity to not just think about or see the advantages and challenges of interdisciplinary research, but to actually participate in them in real time.

Participating students have the chance to play a role in research outputs, either as co-authors or independently. The Valle Gianni Field School seeks in particular to encourage undergraduates who might not otherwise consider pursuing graduate-level research in developing research expertise and experience. Ultimately, our approach offers a new model for mentorship at Illinois State University, and beyond, through the participation of other schools in the project such as Travelers’ Lab research students from Wesleyan University.

The Role of Wesleyan University Traveler’s Lab Students

The Valle Gianni project requires a database platform which is at once capable of storing diverse types of data while also being capable of visualizing that data in specific ways for analysis. This is a complicated undertaking because of the interdisciplinary nature of the venture, and the resulting range of media and data types which the project generates and accumulates.

To this end, we adopted Nodegoat (see: www.nodegoat.net) to manage our data. Nodegoat gives scholars the freedom to generate and analyze datasets based on their own specific, bespoke data models. Moreover, Nodegoat allows relational modes of analysis, which combine both spatial and chronological data. These features make it ideal as a platform for archaeological data.

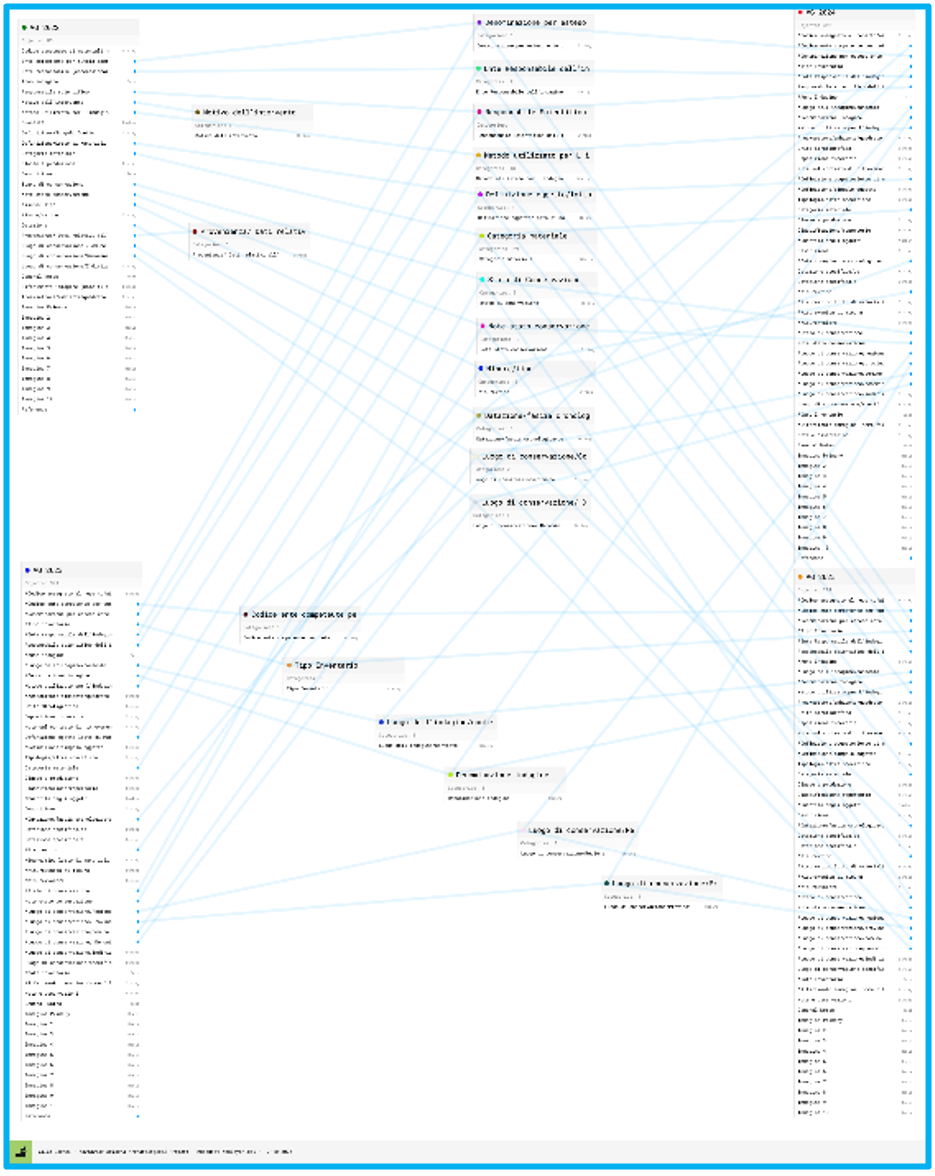

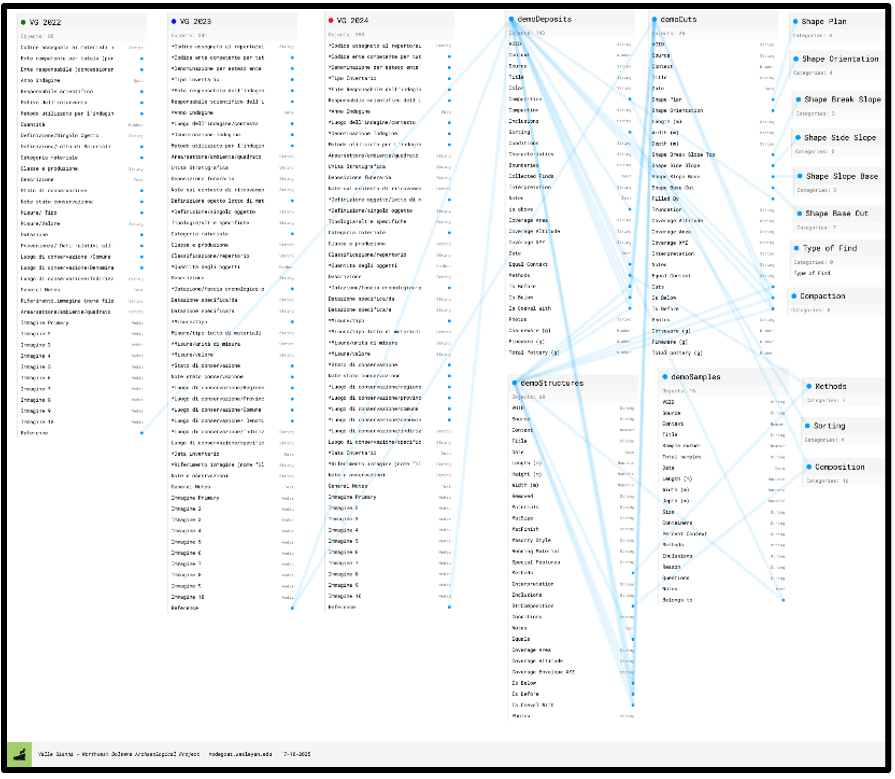

Wesleyan students who trained in the Travelers’ Lab have pioneered the integration of Nodegoat with the Valle Gianni project goals. In 2023 two students—Sarah Brown and Sofia Gallegos—worked together to develop the first relational database model for the Valle Gianni data. Then the following year (in summer 2024) Sarah Brown traveled to Valle Gianni and participated in the Summer Field School’s excavation in order to implement that database live for the first time into the excavation workflow, and to incorporate the new data generated that year.

Most recently, in summer 2025 another Travelers’ Lab student from Wesleyan—Alex Williams—spent four weeks on site. Alex developed an advanced understanding of the archaeological process and how data collection functions on the ground.

Advancing Valle Gianni with Relational Databases in Nodegoat

Specifically, in 2025 Alex Williams addressed herself to integrating the two major types of data which the project generates: data describing physical objects, and digital-born data. Digital-born data include geospatial data (vector and raster), digitized photos—such as photos pertaining to photogrammetry used to produce 3-D digital models—and digitized copies of analogue records generated during the survey, excavation, and subsequent analyses (e.g., site notebooks and excavation diaries), satellite images, and semi-automated data recorded in already-structured machine-readable formats (e.g., spreadsheets and databases).

Other found physical objects include stone, tesserae, ceramics, tile, metal objects, slag and metal derivatives, but also soil samples, botanical remains, faunal remains (including osteological remains and shells), and glass. See some representative excavation photographs below.

Alex Williams’ careful attention resulted in successfully reconciling manual recording practices with the semi-automated generation of digital databases and in this tangible way her work significantly improved the Valle Gianni workflow. The contribution of the Travelers’ Lab students to the Valle Gianni data model can be seen in the comparison, schematized below, of the initial data model through 2024 (black outline) and the comprehensively redesigned, rationalized, and simplified model of 2025 (blue outline) as compiled by Alex Williams.

We regard the accessibility of our data as a critical component of our project. The new developments and components of our workflow have added new facets to the curriculum. These ensure that our data is available, accessible, and as easy to use and understandable (“readable”) as possible. Nodegoat actively helps make this possible. The platform will allow us to transfer data to a public-facing website with intuitive user functions.

The development of our work and processes continues. We continue to refine our databases and their relationality, which in turn opens up new opportunities for new student researchers as well as new types of student research: database design is now a part of the program curriculum.

databases and their relationality, which in turn opens up new opportunities for new student researchers as well as new types of student research: database design is now a part of the program curriculum.

We invite any students interested in helping with this aspect of the project (data management and web design) to apply and inquire about participating in the project, whether during the summer field school or during the academic year. And, of course: all aspiring archaeologists (to right: ISU student Hannah Torkelson) are always welcome to come and help us move dirt around the Italian countryside!